Imagination and Morality in Children’s Picture Book

This essay examines how imagination has been used in children’s picture books across different historical and cultural moments, with a particular focus on the Arab world. It explores how imagination has been shaped, framed, and expressed within specific educational and cultural traditions, and how these traditions continue to influence contemporary practices.

Rather than opposing imagination to morality or education, the essay seeks to understand how imagination functions within children’s literature in the Arab world: how it is perceived, how it is guided, and how much space it leaves for interpretation. It ultimately opens a question about possibility—whether other ways of using imagination can be imagined, ways that place greater trust in the reader’s own perspective and intelligence.

Long before the idea of a “children’s picture book” emerged, stories circulated orally within communities. Myths, legends, fables, and folk tales were shared narratives, addressed to all members of a group rather than to children as a distinct audience. Texts such as The Epic of Gilgamesh, the Panchatantra, and long-standing Arab, Persian, and Chinese storytelling traditions reflect this collective mode of transmission

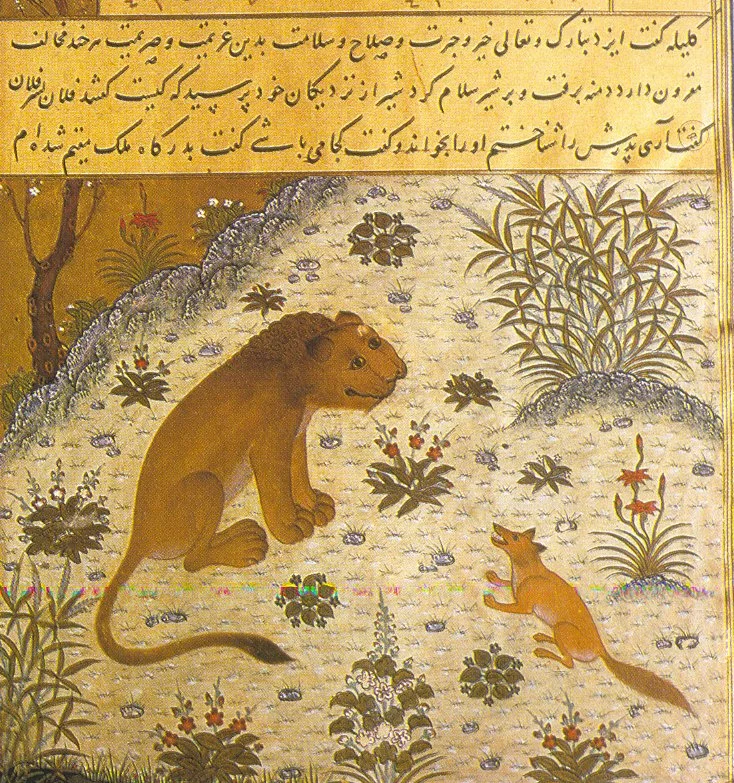

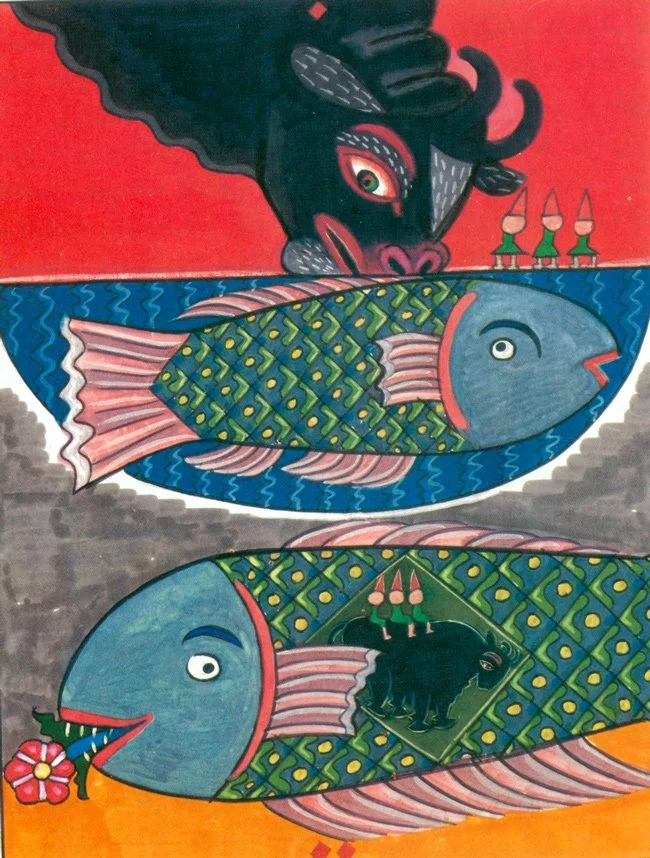

A page from Kelileh o Demneh depicts the jackal-vizier Damanaka ('Victor')/ Dimna trying to persuade his lion-king that the honest bull-courtier, Shatraba(شطربة), is a traitor.

Children were not the primary addressees of these narratives. Nevertheless, they were deeply immersed in them. Through repeated listening, they absorbed symbolic worlds in which imagination, values, memory, and explanations of the world were inseparable.

When Stories Became Educational Tools

As writing practices became more specialized and childhood began to be seen as a distinct stage of life, the function of stories slowly changed. Narratives addressed to children increasingly carried clear educational and moral intentions. The fables attributed to Aesop, as well as Kalila wa Dimna in the Islamic world, mark this transition. Originally composed for adult audiences—often rulers or future rulers—these stories were later reshaped for pedagogical use. They were no longer simply told; they were used.

opening illustration of Master and Child, from the 1705 English edition of Orbis Sensualium Pictus. Source

This shift becomes especially visible in the seventeenth century with projects that sought to organize knowledge itself for children. John Comenius’ Orbis Sensualium Pictus, often described as the first illustrated children’s book, offers a revealing example. Here, words and images work together to present the world as a structured, legible whole. Animals, objects, professions, and moral ideas are arranged, named, and made visible, so that learning can proceed step by step.

Imagination did not disappear in this process, but it was carefully contained. Images were no longer openings into ambiguous symbolic worlds; they became supports for recognition, classification, and instruction. What changed was not the presence of imagination, but its role. Stories and images no longer invited children to inhabit a shared world of symbols; they guided them through a world already ordered in advance.

The case of Lewis Carroll and a New Use of Imagination

A closer look at early European fairy tales, including collections by Charles Perrault and the Brothers Grimm, shows that imagination was often closely tied to moral instruction. Stories that today appear fantastical or magical were built around clear lessons. Good and bad behavior were sharply distinguished, and punishment or reward played a central role. Imagination did not disrupt order; it helped make it visible and understandable.

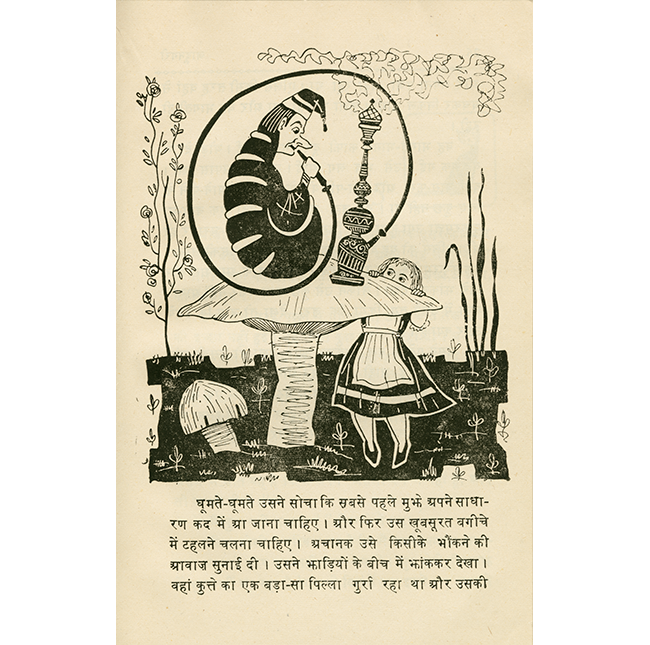

During the nineteenth century, this relationship begins to change. Some works no longer use imagination to guide children toward correct behavior. Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland marks a clear turning point. In Lewis Carroll’s story, nonsense is not a playful way of teaching a lesson. It is simply allowed to exist. The world Alice enters follows strange rules, authority is constantly questioned, and language itself becomes unstable.

Translated into Hindi by Shreekant Vyas. Delhi: Shiksha Bharati, 1979. Source

Alice does not offer chaos. It offers a different way of engaging with meaning and logic. The child reader is not told how to behave or what to understand. Instead, they are invited to explore confusion, contradiction, and play. Imagination is no longer used to support moral clarity; it creates space for experience.

Rather than delivering meaning through explicit lessons, children’s literature gradually develops other ways of addressing its readers. Moral questions and values do not disappear, but they are no longer spelled out in advance. Stories leave more space for experience, and interpretation.

In this context, imagination plays a precise role. It does not oppose logic, morality, or education. It shifts how they operate within the story. Instead of guiding the reader toward a single conclusion, the text assumes their capacity to observe, to question, and to make connections. Meaning is not explained step by step; it takes shape through the reader’s own perspective and intelligence.

What about the Children’s Literature in the Arab World

The development of modern children’s literature in the Arab world followed a specific historical path. It took shape mainly in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, in a period marked by educational reform, language standardization, and broader projects of cultural renewal often associated with the Nahda. At this moment, books for children were closely tied to questions of transmission: how to teach, how to shape conduct, and how to participate in the formation of a modern society.

Early children’s texts were therefore strongly connected to moral, social, and cultural objectives. Stories were expected to instruct as much as to entertain. Imagination was not absent, but it was carefully framed. It served clarity, exemplarity, and the transmission of shared values, rather than ambiguity or open interpretation.

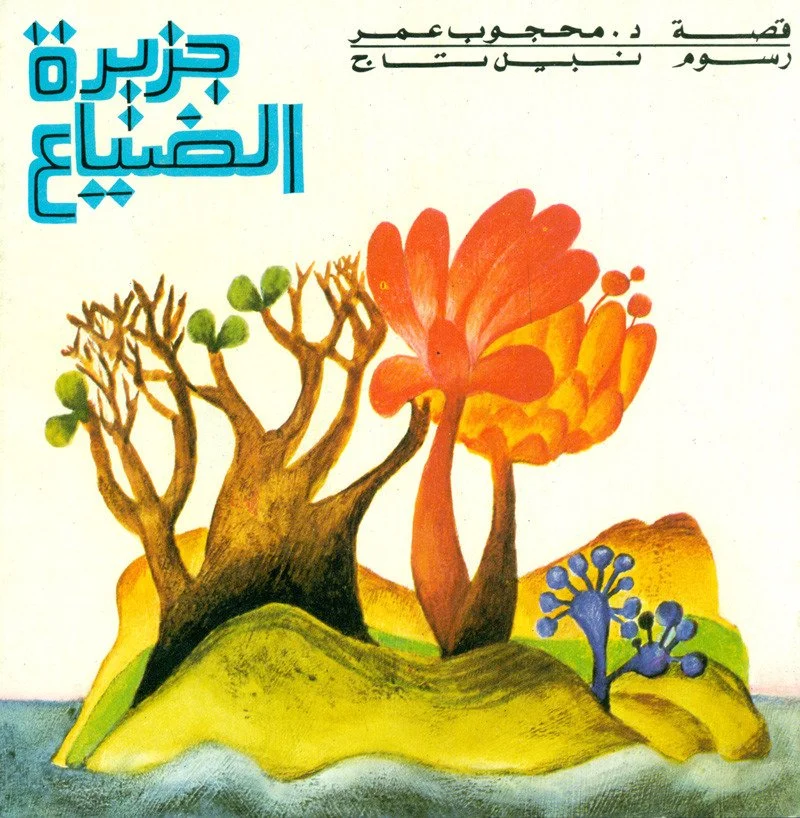

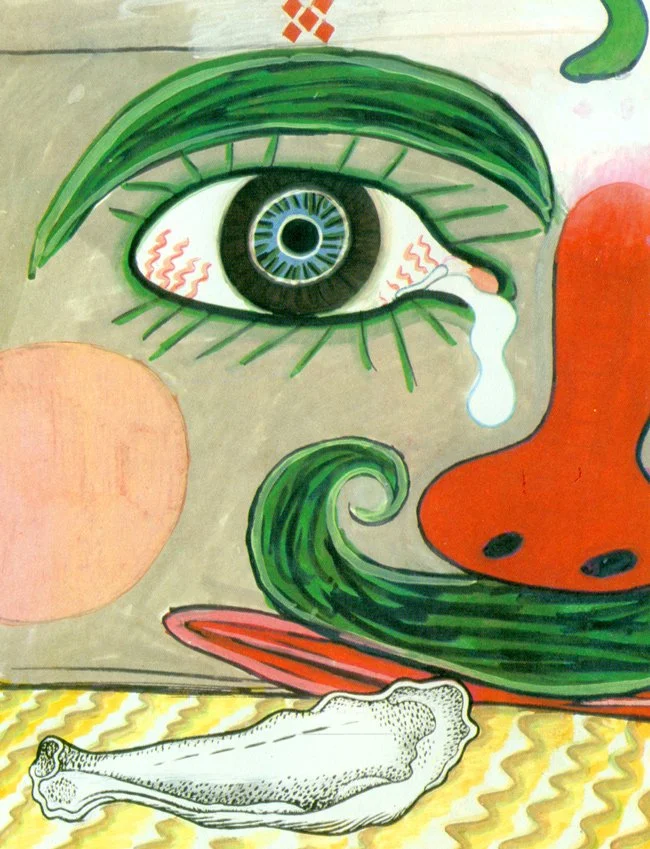

Island of Loss by Mahjoub Omar, illus. Nabil Taj. Via Soorah.

This trajectory should be understood on its own terms. The prominence of educational aims reflects historical priorities rather than a lack of creativity or narrative richness. Stories were mobilized to respond to concrete social needs, and their forms were shaped accordingly. The questions raised about education, imagination, and the role of the child reader were not different, but they were addressed within a distinct historical and cultural framework.

contemporary picture books in the Arab world

Against this historical background, contemporary children’s picture books in the Arab world raise an important question. While forms, formats, and visual languages have evolved, the underlying function assigned to imagination often appears strikingly familiar. Many recent picture books continue to privilege clarity, guidance, and explicit meaning, echoing earlier approaches shaped during the Nahda period.

Imagination is present, sometimes richly so, especially at the visual level. Yet it frequently remains closely aligned with the message the story seeks to convey. Images support the text, reinforce its intent, and help ensure that meaning remains accessible and coherent. Rather than opening space for interpretation, imagination often serves to stabilize understanding.

This continuity does not suggest stagnation, nor does it deny the creative work of contemporary authors and illustrators. It points instead to the persistence of a particular conception of transmission. Imagination is still largely understood as a tool: a way to make values visible, to guide the reader gently, and to avoid misunderstanding. The child reader is addressed with care, but also with caution.

From this perspective, the question is not whether imagination has a place in contemporary Arab children’s literature, but whether it is trusted. Trusted not as an ornament or a pedagogical aid, but as a space in which the reader can interpret, question, and form meaning independently. What remains at stake is not a break with moral or educational concerns, but a shift in how much autonomy is granted to the reader’s own perspective and intelligence.